Paddling the Oconee River

On Saturday we went on a wonderful kayak trip on the Oconee river with Oconee Joe. If you enjoy what I describe you should look him up www.oconeejoe.com . It was a bluebird, chamber of commerce day. The slight overcast gave away to blue skies and a light, but increasing breeze. Our group was small and the goal was to experience the river. This leisurely pace enabled us to experience the current, the blooms, and the history of the stretch.

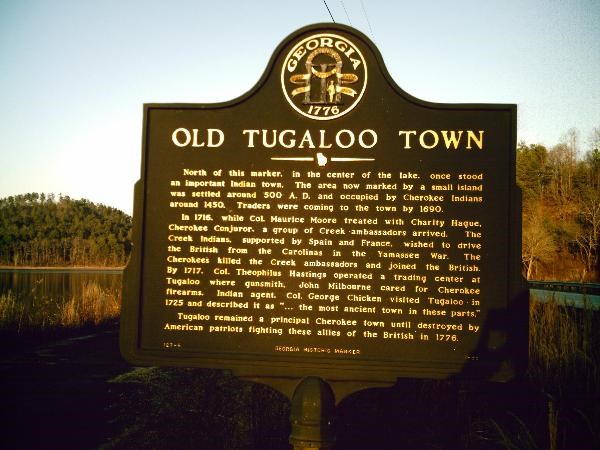

The trip began on the Middle Oconee River near Macon Highway. A sandy, but steep bank made for a good entry to the river and ample time to brief about the plan for our trip. The green buds of spring were in various stages depending on the species of flora and we saw the tracks left by the recent visit of beavers and deer. The launch was near the original Paper Mill and Princeton Factory site. The old bridge was the site of the only significant civil war action in Athens where Union Cavalry engaged the local militia, but were unable to force a crossing of the Oconee River.

In July of 1864, General Sherman ordered an operation to cut Atlanta’s railroad supply lines. Maj. Gen George Stoneman, with three cavalry brigades (2112 men and 2 guns) was given the task. He successfully destroyed the railroad in Gordon, McIntyre and Toomsboro burning trains, supplies, and the railroad bridge over the Oconee River. At Macon, he was repulsed and began a retreat. On July 31st Stoneman was outmaneuvered by Confederate forces at the Battle of Sunshine Church. As a result, Stoneman allowed himself to be captured along with 600 of his men to effect the escape of Adams’ and Capron’s brigades. Capron and Adams moved north and developed a plan to attack Athens since it hosted an armory. Adams attempted to cross the bridge over the Middle Oconee, but was unsuccessful account the preparations that Confederate forces had made to defend Athens. Adams turned his brigade North and reach Marietta to rejoin Union Forces. Capron was in Watkinsville holding in reserve for the attack on Athens. He attempted to follow Adams route back to Union lines, but instead too the Hog Mountain road which was further west. Although he was being pursued by the “Orphan Brigade”, Capron allowed his troops to rest for a few hours at the Mulberry River crossing. This crossing is about ½ mile South of Bethabara Church. As the troops rested, the Confederates attacked and routed Capron’s men who fled across the Mulberry Bridge along with a group of fleeing slaves. The Bridge collapsed and most of the Union cavalrymen became prisoners. Capron and 6 of his men made to union lines four days later on foot.

Leaving the site of the battle we paddled south down the river. Our next land mark would be McNutt’s creek. The creek has a strong flow and joins the river at the Botanical Gardens. We saw a group from the Audubon Society counting birds and we received a warm hello from the group. Cardinals and Kingfishers darted around the banks as we made our way through this area. The strength of McNutt’s creek gave endorsement to the record of Mills in this water shed. Aside from the Paper Mill which was near the spot, Princeton Factory was also on the Middle Oconee and not far overland on the north branch, the Georgia Factory was present thanks to good waterflow. The difference in the control of water is evident when comparing the photos from our trip to the 1919 photo of the Oconee. Trees are overhanging a little more in 1919, and the bank is not as eroded. Although cotton production did cause erosion in years past, the impervious surface creation in recent decades has caused a much greater rate of change of river levels resulting in growth being unable to establish itself on the banks of the river. The 1938 USDA aerial photographs show a good amount of timber growth in the watershed interspersed with terraced farming.

After passing by the botanical gardens we took a nice break on a sand bank. It was a chance to take in the scenery and review one of the coolest things we saw, a rookery. We were able to see a wonderfully tall and spreading tree with at least eight Blue Heron nests. They were grand. Built high in the air and constructed of large sticks the sight was marvelous. The long legged herons were humorously graceful as they walked and jumped among the branches. Herons pair up for the nesting season and partner to protect the nest. The cackling and ticking sounds they made were a unique symphony all their own.

Our movement on the river let us paddle by the old foundations for Simonton Bridge. The stacked stones are only a few yards north of the present day Simonton Bridge Road/ Whitehall Road bridge. Calls creek enters the Middle Oconee on the stretch. The USDA Photographs show the bridge and the approach roads. We continued to row downstream to my favorite infrastructure of the day, the railroad bridge. The wrought iron structure is a living example of 19th to 20th century bridge construction. In the 1880s the Macon and Covington Railroad acquired the property from John White and SP Reeves and bridged the Middle Oconee River to get access to Athens. The current bridge was not the first structure the railroad built. Buried in the banks is riveted boilerplate cylinders. There were used as footer foundations for the original timber bridge. Bents from the old timber bridge approach are visible on the East side of the river, there are also bolts associated with timber structures in the soil surrounding the structure. Around 1922, the east side approach was filled in with dirt and the new concrete piers were added to serve as supports for the current bridge. The rail that carried trains over the bridge was rolled in 1907 in Maryland. A more modern steel beam structure now carries the tracks from the end of the fill to the current bridge piers. Two centuries of engineering are well worth the few minutes of stoppage.

Leaving the rail bridge, we traveled a quarter mile downstream and took a break on the sandbar at the confluence of the Middle and North Oconee. Aside from the river junction, the John White power station is a great highlight of this spot. We were able to walk and explore the site. John or James White constructed the dam in the early 1900s to produce hydroelectricity. The Dam spanned the Middle Oconee just above the confluence of the Middle and the North branches. The water intake was on the east shore and the power house was designed as a turbine mine. The turbine was submerged in the basement of the building with a shaft extending to the first floor. On the first floor of the powerhouse, the turbine shaft extended to a junction by gear with a horizontal shaft. Connected to that shaft was a pulley with a series of V belts. The v belts connected the pulley to another pulley on the 2nd floor. That shaft connected to a Westinghouse Generator and thus power was created. In 1910, the Athens Railway and Electric Company Leased the site for a term of 99 years. After falling out of use the site was left unattended until July of 2018 when the central part of the dam was removed allowing the Middle Oconee to free flow again.

The pause at the sandbar gave us time to talk about the river’s story and enjoy the beauty of the dozens of Tiger Swallowtail butterflies. I found a small piece of clay there that was part of some sort of rounded feature. The sand that has silted from the middle and north rivers forms up nicely and the current filters away quickly at the edges exposing heavier objects. The smoked Gouda cheese we enjoyed was outstanding and it paired nicely with the peanut butter and jelly sandwich I packed from home.

The river from here to our takeout point grew wider at each turn. We passed several nice rock features that would be great for climbing or pondering. The surroundings provided plenty of natural sounds as the industrial noise of the city drifted away. I took the leisure of being the last boat in line and the last to exit the water. We took out above Barnett Shoals. Had I been at this spot in 1795 it would have been safer in the river, or at Fort Matthews. The Fort would have been nearby, but we are not sure exactly. It was a nice day. As always it left me longing for more. I can’t wait to see what the next trip brings.

August 3rd from the Southern Watchman in Athens describing the Union Cavalry near Athens, note the reference to the Paper Mill.

Information from the National Railway Guide mentioning James White’s Power Company in 1910.

Covington and Macon Railroad bridge over the Middle Oconee. In this drawing North is at the bottom of the picture.

In this 1868 map of Clarke County you can see the location of Paper Mill and just below it the confluence of the Middle and North Oconee Rivers.

A Map date circa 1930, the location of Simonton’s Bridge and the Railroad Bridge are visible.

This 1890 USGS map shows the community of Algernon which is where the Battle of King’s Tanyard occurred after Capron’s Cavalry left Athens on August 2, 1864.

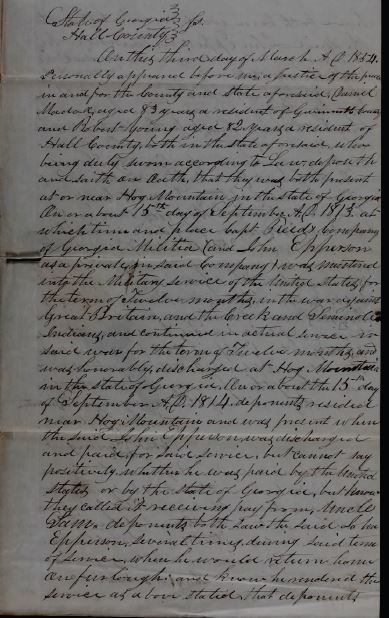

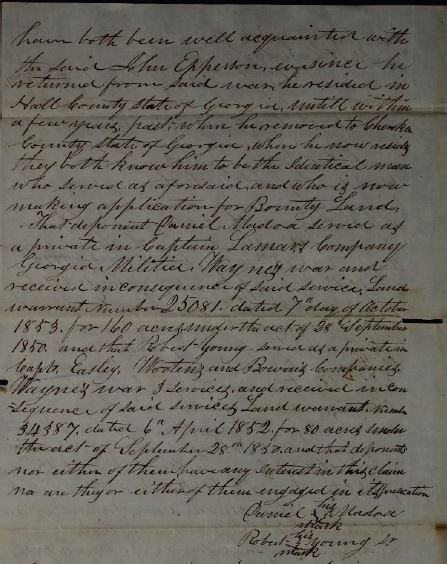

Deed for John White’s land to the Railroad crossing on the Oconee.

Westinghouse Generator on the 2nd Floor of the White Powerhouse. Probably 1904 vintage.

A Blue Heron Rookery.

Just After setting out, near the site of the Cavalry skirmish.

White Powerhouse.

Bridge Piers from the old Simonton Road Bridge.

Railroad Bridge looking West from the Clarke Bank towards Oconee County.

Riveted Boilerplate from the 1890s railroad bridge.

Closer view of the bridge structure

White Dam and powerhouse with center of Dam removed.

![IMG_5030[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b8dd8638ab7225fc2cb4989/1548293424911-N3D3Y8O0C9FW4U2TET9E/IMG_5030%5B1%5D.JPG)